The Quadriune Godhead: A Universal Divine Presidency Rooted in All Faiths

Section I: Introduction – Recovering the Quadriune Pattern

Across time, geography, and spiritual tradition, humanity has preserved the memory of a divine structure more ancient than dogma and more universal than creed—not monotheistic and singular, not trinitarian and patriarchal, but quadriune: a godhead composed of four coequal personages. This presidency of four appears again and again in the architecture of temples, the cycles of the heavens, the symbolism of sacred texts, and the governance of ideal communities.

In this paper, the term quadriune refers to a divine model of presidency—not hierarchy or monarchy. It is not a mystery of one being in four manifestations, nor a trinity of masculine persons, but rather four eternal beings bound in covenantal unity. These four roles—Lawgiver, Nurturer, Redeemer, and Counselor—are functions, not titles; they rotate, cooperate, and represent the full spectrum of divine purpose. Each human can find their reflection in one or more of these roles, regardless of gender, life stage, or relationship status.

This quadriune order is not an invention of modern theology. It is a universal memory, found in:

– The Sumerian tetrad of An, Ki, Enlil, and Inanna[1];

– The Egyptian arrangement of Osiris, Isis, Horus, and Ma’at[2];

– The Vedic deities Vishnu, Lakshmi, Krishna, and Saraswati[3];

– The Taoist cosmogram of Heaven, Earth, Humanity, and Spirit[4];

– The Hebrew and early Christian pattern of YHWH, Ruach, Logos, and Chokhmah[5];

– The Indigenous world’s directional and ceremonial quadrants—often led by rotating councils of four[6].

This pattern is remembered in the architecture of pyramids and mandalas, in the four faces of the divine throne (Ezekiel 1; Revelation 4)[7], in the four elements, seasons, winds, gospels, empires, noble truths, and sacred altars. Even modern psychological models (Jung)[8], constitutional systems (Roman and Iroquois)[9], and celestial calendars (zodiac, solstices, medicine wheels)[10] reflect the same symmetry.

This paper argues that the Quadriune Godhead is not a theological curiosity but a cosmic constitution. It governed ancient heaven and ancient cities alike. Its loss—through imperial monotheism, masculine trinitarianism, and ecclesiastical centralization—was a distortion, not a development.

Joseph Smith, in the early years of his revelatory work, began to restore this pattern. Though his later turn to patriarchy and polygamy derailed the vision, his earliest revelations—the Law of 1831, the Plat of Zion, and Section 94’s twin buildings with four identical courts—all reflect the quadriune model. It is in these early texts, not later innovations, that a blueprint for divine community and divine identity survives.

To rediscover the quadriune is to remember a truth older than empire, more inclusive than priesthood, and more balanced than kingship. This paper is a call to remembrance: of the Godhead of Four, and the world it was meant to govern.

References – Section I

1. Samuel Noah Kramer, The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character (University of Chicago Press, 1963).

2. Geraldine Pinch, Egyptian Myth: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2004).

3. Stella Kramrisch, The Hindu Temple (Motilal Banarsidass, 1976).

4. Chad Hansen, A Daoist Theory of Chinese Thought (Oxford University Press, 1992).

5. David Winston, The Wisdom of Solomon: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary (Yale University Press, 2007).

6. Barbara Alice Mann, Iroquoian Women: The Gantowisas (Peter Lang, 2000).

7. Ezekiel 1:5–10; Revelation 4:6–8 (KJV).

8. Carl Jung, Man and His Symbols (Doubleday, 1964), pp. 215–237.

9. Donald A. Grinde and Bruce E. Johansen, Exemplar of Liberty: Native America and the Evolution of Democracy (UCLA American Indian Studies Center, 1991).

10. E.C. Krupp, Echoes of the Ancient Skies: The Astronomy of Lost Civilizations (Oxford University Press, 1983).

Section II: Sumerian and Akkadian Witnesses to the Quadriune Pattern

The Sumerian and Akkadian civilizations of Mesopotamia—flourishing from the late 4th millennium BCE through the early 2nd millennium BCE—offer the earliest substantial textual, liturgical, and architectural records of organized religion. Their surviving myths, hymns, temple inscriptions, and administrative texts describe a cosmos that is governed not by a single god nor by a rigid hierarchy of many, but by a dynamic, interrelated network of deities. These deities were distinct in function, often gendered, and situated within a cooperative model of divine balance.

At the head of this divine system was An (Anu), the celestial father, associated with law, kingship, and the immutable divine order. His partner was Ki (later known as Antu), the personification of the earth and mother of the gods. Their union produced the next generation of divine figures, including Enlil, god of air and executive force, and Inanna (later Ishtar), goddess of love, fertility, and war. Significantly, Inanna was unmarried—a status highlighted repeatedly in her rituals and myths.

This divine quad—An, Ki, Enlil, and Inanna—appears consistently across Sumerian city pantheons and temple cults. An and Ki represented the stable married foundation, while Enlil and Inanna embodied the redemptive and prophetic forces. Their roles were not merely symbolic: temple rituals, political decrees, agricultural festivals, and royal legitimization ceremonies were built on this balanced interplay. For example, the sacred marriage (hieros gamos) rituals between kings and high priestesses invoked these patterns in temple states such as Uruk and Nippur.

Inanna’s role especially demands attention. Her mythic descent into the underworld, death, and resurrection (Descent of Inanna, ETCSL 1.4.1) is the earliest known death-and-rebirth narrative in religious literature. She navigates between worlds, negotiates with male judges, and ultimately resurrects by consent of a divine council. In some texts, she even overrules the authority of Enlil. Inanna is not a consort but a sovereign, a female divine personage with independent prophetic authority—thus representing the counselor archetype of the Quadriune structure.

Meanwhile, Enlil acts as a mediator between the fixed order of An and the chaos of the world. He issues decrees, appoints rulers, and enforces balance. In Akkadian texts, Enlil’s role expands to include cosmic arbitration, resembling both a divine judge and redeemer—a role echoed later in figures like Horus, Vishnu, and Christ.

Sumerian cosmology was not a loose pantheon—it was a structured presidency of four archetypal beings:

– An (Married Male): Lawgiver, sky deity, source of decree.

– Ki (Married Female): Earth mother, co-creator, stabilizer of generative power.

– Enlil (Single Male): Mediator, executive force, judicial redeemer.

– Inanna (Single Female): Counselor, warrior, fertility priestess, inspirer of transformation.

This structure is not only conceptual but is mirrored in physical architecture: the temple complexes at Uruk (Eanna precinct), Nippur, and Eridu each contain cult chambers and ritual courtyards aligned to these figures. Seasonal festivals were timed to their interactions, and divine rulership (the me) was assigned through divine council decrees that included all four roles.

Scholars such as Jean Bottéro and Thorkild Jacobsen emphasize that the Sumerian model was not polytheistic chaos, but a deeply ethical, balanced system. Jeremy Black’s symbolic analysis links these figures to cosmic functions that align closely with later philosophical systems from Egypt, Greece, and Vedic India. The godhead was not static or singular—it was a living system of divine checks and balances, a pattern that closely parallels the structural integrity of the Quadriune Godhead.

Modern readers cannot afford to passively dismiss these systems as primitive or obscure. These were engineered spiritual constitutions, refined through centuries of oral and textual tradition, and institutionalized across multiple city-states. They provide the earliest evidence of a divine presidency—not metaphorical, but liturgical, political, and architectural. To ignore this fourfold structure is to reject the foundational grammar of the sacred in early civilization.

References – Section II

[1] Diane Wolkstein and Samuel Noah Kramer, Inanna: Queen of Heaven and Earth – Her Stories and Hymns from Sumer (Harper & Row, 1983), pp. 3–75.

[2] Jean Bottéro, Religion in Ancient Mesopotamia (University of Chicago Press, 2004), pp. 76–144.

[3] Thorkild Jacobsen, The Treasures of Darkness: A History of Mesopotamian Religion (Yale University Press, 1976), pp. 125–146.

[4] Jeremy Black and Anthony Green, Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia (University of Texas Press, 1992), pp. 34–67.

[5] Samuel Noah Kramer, History Begins at Sumer (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1981), pp. 151–172.

[6] A.R. George, House Most High: The Temples of Ancient Mesopotamia (Eisenbrauns, 1993), pp. 44–85.

Section III: Egyptian Divine Council and Cosmic Balance

The theological system of ancient Egypt presents a highly structured, deeply symbolic, and philosophically rich vision of divine order. Flourishing from ca. 3000 BCE to the Greco-Roman period, Egyptian religion did not worship a single god nor a chaotic polytheism, but rather a pantheon organized around cosmic roles, divine partnerships, and a logic of balance (ma’at). Within this structure, the concept of a fourfold divine presidency emerges not only implicitly, but explicitly in their myths, iconography, and temple design.

Among the many gods and goddesses of Egypt, four stand out as forming a persistent and recurring divine council, especially in Osirian theology:

– Osiris – God of death, kingship, judgment, and resurrection. Represents the stable male lawgiver and just ruler (Married Male).

– Isis – Wife of Osiris, goddess of motherhood, healing, and magic. Co-creator and divine nurturer, who restores Osiris and births Horus (Married Female).

– Horus – Son of Osiris and Isis, a sky god and avenger who reclaims justice. Often unmarried, representing a warrior-redeemer (Single Male).

– Ma’at – Goddess of truth, cosmic balance, and morality. She stands as the feminine embodiment of counsel, judgment, and inspiration (Single Female).

These four figures are not mere narrative devices; they are central to temple rites, funerary rituals, and the moral architecture of the Egyptian worldview. In the Book of the Dead (chapters 125 and 130), Ma’at governs the weighing of the heart. Osiris presides over the court of the dead. Isis restores divine continuity. Horus battles for cosmic order. Together, they mirror the structure of a constitutional divine presidency, not unlike the model of the Quadriune Godhead.

The centralization of these four in temple space is evident in major cult centers:

– At Abydos, the temple of Osiris features side chapels and sanctuaries dedicated to Isis and Horus.

– In Philae, the Ptolemaic temple to Isis includes integrated reliefs of Ma’at being presented to gods as the sustaining principle of cosmic justice.

– Ritual reenactments of Osiris’s death and resurrection in annual festivals at Abydos and Dendera involved the entire narrative arc of the four beings.

Importantly, Ma’at was not depicted as a mythic subordinate but as a foundational principle. Kings “lived by Ma’at,” offerings were “in Ma’at,” and governance was “under Ma’at.” Her personification appears not as a consort or maternal figure but as truth incarnate—female, single, and sovereign. As Egyptologist Erik Hornung notes, “Ma’at is the very substance of order; the world was made and is sustained through her.”[1]

Unlike Hellenistic rationalism or later monotheism, Egyptian theology did not attempt to fuse all divine roles into one being. It preserved differentiation without hierarchy, allowing gods to maintain separate functions while acting in mutual interdependence. The Osirian council reflects not a chain of command, but a circle of responsibility:

– Osiris decrees,

– Isis restores,

– Horus vindicates,

– Ma’at judges.

Theologically, this structure preserves moral accountability and relational governance. It establishes the divine as a system of checks and restoration—not domination.

In summary, the Egyptian model provides a fully realized quadriune structure: cosmically, ritually, philosophically, and politically. The divine presidency is not accidental but constitutive of Egyptian sacred thought.

References – Section III

[1] Erik Hornung, Conceptions of God in Ancient Egypt: The One and the Many (Cornell University Press, 1982), pp. 147–175.

[2] Geraldine Pinch, Egyptian Myth: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2004), pp. 88–101.

[3] James P. Allen, Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs, 3rd ed. (Cambridge University Press, 2012), pp. 407–418.

[4] Jan Assmann, The Search for God in Ancient Egypt (Cornell University Press, 2001), pp. 71–106.

[5] Raymond Faulkner, trans., The Egyptian Book of the Dead: The Book of Going Forth by Day (Chronicle Books, 2000), pp. 34–45, 89–92.

Section IV: Vedic and Hindu Divine Complements

The religious and philosophical systems of ancient India—expressed through the Vedas, Upanishads, Puranas, and epic narratives such as the Mahabharata and Ramayana—preserve one of the richest traditions of divine plurality in the world.

While Hinduism allows for monistic interpretation (as in Advaita Vedanta), it has always accommodated a robust theistic realism, wherein gods and goddesses exist in relationship, enacting the eternal roles of preservation, destruction, wisdom, wealth, and compassion.

Classical Hinduism organizes many of its deities as dyadic complements—masculine and feminine, married and distinct—forming the basis of balance in the universe. The most prominent of these pairs include:

– Vishnu and Lakshmi – Vishnu is the preserver, ruler of cosmic order (dharma); Lakshmi is the goddess of abundance, wealth, and fertility.

– Shiva and Parvati – Shiva is the ascetic, destroyer, and yogi; Parvati (also Durga) is the fierce protector, mother goddess, and warrior.

However, within these dyads emerge two singular archetypes that fulfill distinct roles not contingent on marriage:

– Krishna, a form of Vishnu, operates often in bachelor form—as a divine redeemer, friend, and teacher (e.g., his role in the Bhagavad Gita). Though associated with Radha, he is never formally married to her, emphasizing his status as a divine single male who redeems and inspires.

– Saraswati, goddess of knowledge, speech, music, and wisdom, is often unmarried in her independent form and revered as a single female personification of inspired insight. Temples dedicated to Saraswati often exclude depictions of consorts, reinforcing her autonomy.[1]

These four divine roles—Vishnu, Lakshmi, Krishna, Saraswati—can be mapped onto the Quadriune Godhead as follows:

Lawgiver (Married Male): Vishnu – Cosmic order, preservation, dharma

Nurturer (Married Female): Lakshmi – Abundance, prosperity, generative care

Redeemer (Single Male): Krishna – Teacher, servant, restorer of balance

Counselor (Single Female): Saraswati – Wisdom, music, inspiration, knowledge

In the Bhagavad Gita (especially chapters 3–4), Krishna instructs Arjuna on the moral structure of the cosmos, functioning as both redeemer and counselor, bridging divine law and personal freedom. His role is intimate, dialogic, and catalytic—fitting the single redeemer archetype.[2]

Lakshmi and Vishnu are invoked together in domestic rituals and harvest festivals such as Diwali, symbolizing wealth and order. Their combined worship signifies a stable, married pairing—lawgiver and nurturer—who bless and preserve household and society.

Meanwhile, Saraswati is worshipped separately during Vasant Panchami, where students, musicians, and seekers pray for insight and clarity. She is not petitioned for children or marriage, but for eloquence and enlightenment, reflecting her role as independent inspirer.[3]

In temples, this quadriune division often manifests in shrines and iconography:

– Vishnu and Lakshmi share sanctuaries in Vaishnavite complexes.

– Shiva and Parvati are united in composite images (e.g., Ardhanarishvara), yet worshipped distinctly.

– Saraswati’s temples (e.g., in Tamil Nadu and Gujarat) present her alone, usually seated on a swan or lotus.

– Krishna, especially in ISKCON and Bhagavata traditions, stands apart as a singular god of playful wisdom and strategic redemption.

Indian thought does not bind divinity to hierarchy. The Shakta tradition even inverts gender norms, portraying the goddess as superior.

But what remains across traditions is the necessity of divine balance. The masculine cannot act without the feminine. The redeemer is not the ruler. The wise are not necessarily married.

The godhead is not complete unless each quadrant of cosmic function is present.

This presents a non-trinitarian, non-hierarchical, but deeply structured understanding of divinity—one that echoes the Quadriune Godhead pattern.

Such a structure is not speculative. It is evident in daily Hindu practice, from the names children are given, to the offerings made in festivals, to the architecture of sacred space. Hinduism preserves the quadriune model not only in text but in life.

References – Section IV

[1] David Kinsley, Hindu Goddesses: Visions of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Tradition (University of California Press, 1986), pp. 17–72.

[2] Eknath Easwaran, trans., The Bhagavad Gita, 2nd ed. (Nilgiri Press, 2007), esp. chapters 3–4.

[3] June McDaniel, Offering Flowers, Feeding Skulls: Popular Goddess Worship in West Bengal (Oxford University Press, 2004), pp. 198–225.

[4] Gavin Flood, The Truth Within: A History of Inwardness in Christianity, Hinduism, and Buddhism (Oxford University Press, 2013), pp. 61–84.

[5] Wendy Doniger, The Hindus: An Alternative History (Penguin Press, 2009), pp. 144–182.

Barbara Tedlock, The Woman in the Shaman’s Body (Bantam Books, 2005).

Section IVa: Architectural Echoes of the Quad

Throughout human history, sacred geometry and divine governance have often converged in one enduring archetype: the four-sided structure, oriented to the cardinal directions. This architectural quadrature—found in pyramids, temples, city grids, shrines, earthworks, and even homes—expresses an intuitive reverence for fourfold balance. It is one of the oldest and most universal expressions of spiritual order.

The Egyptian pyramid, with its four identical triangular faces aligned to the cardinal directions, is perhaps the most iconic religious structure in human history. Egyptologists such as Mark Lehner and Zahi Hawass note that this form was not merely structural—it was symbolic of cosmic order. The four sides represented the four sons of Horus, guardians of the organs and of the earth’s compass points.

The pyramid was the king’s vehicle to ascend to the heavens—anchored in fourfold earth, rising into unity.

In Mesoamerica, the Mayan and Aztec pyramids follow the same four-sided logic. The Temple of Kukulkan in Chichen Itza features staircases on four sides and is precisely aligned with equinoxes and solstices. It embodies the four quarters of the cosmos in Mayan belief: north (white), south (yellow), east (red), west (black)—each direction governed by a deity.

Similarly, the Nubian pyramids of Kush and the step pyramids of Mesopotamia (ziggurats) were built on square bases, rising from four gates—suggesting access to heaven via a unified but plural foundation.

Across Asia, temples often manifest a four-portal structure, with entrances aligned to cardinal directions. The Hindu mandala—used as a blueprint for temple design—centers on a square subdivided into four equal zones. The Sri Yantra likewise divides divine space into quadrants, representing Shiva, Shakti, Vishnu, and Brahma as co-governing aspects of the divine.

The Khmer masterpiece Angkor Wat is aligned with solstices and surrounded by four towers and causeways, symbolizing cosmic balance. Chinese Taoist temples place altars and gates according to the Sì Xiàng (Four Symbols)—Azure Dragon (east), White Tiger (west), Vermillion Bird (south), and Black Tortoise (north)—each an emblem of cosmic function.

Early Christian basilicas were built on cruciform (four-armed) plans, with central domes at the intersection—mapping the human body and divine cosmos as quadrated wholes.

Most human dwellings—across eras and geographies—are built on a rectilinear base with four primary walls. Anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss noted that this is not merely practical—it reflects a cognitive structure of oppositional balance and navigational orientation.

In Indigenous North America, mound-building cultures embedded this fourfold symmetry in sacred landscapes. The Cahokia Mounds in Illinois include Monks Mound, a four-sided platform mound oriented to the cardinal points, with a city layout reflecting cosmogrammatic order. Timothy Pauketat describes Cahokia as a cosmologically ordered civic center reflecting sacred spatial philosophy.

At Poverty Point in Louisiana, earthworks were built with fourfold orientation to celestial cycles. Jon Gibson argued that these designs expressed ritual landscapes aligned to the sun, creating temporal and directional balance.

The Hopewell culture of Ohio created large square enclosures and mounds aligned with solstices and the four directions. Bradley Lepper identifies these as symbolic constructions reflecting a unified cosmology.

In Indigenous traditions, such as among the Lakota, Zuni, and Navajo, dwellings (tipis, hogans) are constructed with spiritual zones mapped onto the four directions. Entrances face east. The interior reflects sacred cosmograms.

In medieval Europe, town centers featured cross-shaped plazas dividing neighborhoods into four parishes. Islamic architecture used the chahar bagh (four-part garden) to symbolize Eden and paradise through four flowing streams.

The Plat of Zion is a modern echo of this pattern. Designed by Joseph Smith under revelation, it divides a community into four quadrants with a central temple complex. The city plan is governed by four-person presidencies per agency, turning the city into a livable mandala of governance and divine symmetry.

Scholars like Mircea Eliade, Paul Wheatley, and Numa Denis Fustel de Coulanges have shown how sacred cities reflect divine constitution—divided into quadrants representing spatial function, ritual hierarchy, and theological balance.

The four-sided base, oriented to the cosmos, symbolizes the stable, eternal governance of the divine. The ascent of a structure (pyramid, dome, or tower) represents movement toward divine unity—but only if rooted in foundational balance.

In this, the fourfold base reflects the Quadriune Godhead:

– East: Counselor (vision)

– South: Redeemer (sacrifice)

– West: Lawgiver (judgment)

– North: Nurturer (sustenance)

These directional alignments appear across cultures in theology, architecture, and sacred design. That human beings consistently build with four sides and four cardinal references is not arbitrary—it reflects a memory of divine order inscribed in the physical world.

Architecture becomes theology in form. The quadrated base is the signature of the Godhead in stone, soil, and space.

References – Section IVa

1. Mark Lehner, The Complete Pyramids (Thames & Hudson, 1997), pp. 84–99.

2. Anthony F. Aveni, Skywatchers of Ancient Mexico (University of Texas Press, 2001), pp. 153–178.

3. Stella Kramrisch, The Hindu Temple (Motilal Banarsidass, 1976), pp. 1–56.

4. Eleanor Mannikka, Angkor Wat: Time, Space, and Kingship (University of Hawaii Press, 1996).

5. Claude Lévi-Strauss, The Savage Mind (University of Chicago Press, 1966), pp. 113–136.

6. Timothy R. Pauketat, Cahokia: Ancient America’s Great City on the Mississippi (Penguin Books, 2010).

7. Jon L. Gibson, Poverty Point: A Terminal Archaic Culture of the Lower Mississippi Valley (Louisiana State University Press, 2000).

8. Bradley T. Lepper, Ohio Archaeology: An Illustrated Chronicle of Ohio’s Ancient American Indian Cultures (Orange Frazer Press, 2005).

9. Emma Clark, The Art of the Islamic Garden (Interlink Books, 2004), pp. 42–58.

10. Mircea Eliade, The Sacred and the Profane (Harcourt, 1959); Paul Wheatley, The Pivot of the Four Quarters (University of Chicago Press, 1971).

Section IVb: The Fourfold Cosmos – Calendars, Stars, and the Architecture of Time

Just as the four-sided pyramid and quadrated city mirror the divine structure in space, so too do humanity’s oldest timekeeping systems mirror the Quadriune pattern in time. From Neolithic monuments to zodiacal cosmologies, from agricultural festivals to sacred rites, cultures across the globe have organized their lives around fourfold rhythms. These patterns reflect more than utility—they encode a symbolic memory of divine presidency, linking the cycle of time with the structure of heaven.

The division of the year into four seasons—spring, summer, autumn, winter—is nearly universal. Each season is not only a climatic reality but a ritual archetype:

– Spring: Vision, birth, and planning (Counselor)

– Summer: Growth, energy, abundance (Nurturer)

– Autumn: Harvest, reflection, law (Lawgiver)

– Winter: Death, rest, sacrifice (Redeemer)

In the Celtic Wheel of the Year, the solstices and equinoxes are joined by four cross-quarter days, creating an eight-spoke cycle whose foundation is quadrated. In the Hebrew tradition, feasts such as Passover, Pentecost, Rosh Hashanah, and Sukkot align with agricultural and celestial rhythms—each reflecting divine roles across a yearly pattern.

Zodiacal systems also reflect quadrature. In Babylonian and Greco-Roman cosmology, the twelve signs of the zodiac are divided into four elemental triplicities:

– Fire: Aries, Leo, Sagittarius (Counselor)

– Earth: Taurus, Virgo, Capricorn (Lawgiver)

– Air: Gemini, Libra, Aquarius (Redeemer)

– Water: Cancer, Scorpio, Pisces (Nurturer)

These quadrants correlate with directions, elements, and life phases. In Chinese cosmology, the Four Palaces governed by celestial beasts—Azure Dragon (East), Vermillion Bird (South), White Tiger (West), and Black Tortoise (North)—establish a similar fourfold correspondence between stars, seasons, virtues, and societal roles.

The Book of Enoch describes four archangels who govern the celestial realm. Mesopotamian texts similarly record four ‘royal stars’ used to mark equinoxes and solstices. Early Christians encoded four divine aspects in the tetramorph: the man (Matthew), lion (Mark), ox (Luke), and eagle (John)—symbols echoed in both Ezekiel and Revelation.

Horoscopic cults in Zoroastrian, Mithraic, and Chaldean contexts revolved around celestial presidency. Zoroastrianism identifies four Amesha Spentas—each stewarding a cosmic domain under Ahura Mazda. Gnostic cosmology features the divine Tetrad—four Aeons governing the Pleroma. In Roman Mithraism, zodiacal quadrature surrounds the tauroctony, with four animal guardians echoing divine functions.

Astronomical monuments such as Stonehenge, Nabta Playa, and the Goseck Circle were aligned to solar quadrants—solstices and equinoxes—marking divine order through the architecture of time. Medicine wheels among Native American cultures map sacred space and time using four cardinal spokes for seasons, winds, life stages, and ritual pathways.

Calendars shaped by these systems reinforced temporal symmetry. The Mayan calendar embedded a base-20 structure into a 260-day sacred round and 365-day solar year, aligning time with directional and functional deities.

This fourfold mapping of the heavens is not only cultural—it is constitutional. In the governance model restored through the 1831 Law and Plat of Zion, a 13-week quarter governs community rotation. Each four-person presidency operates weekly with rotating assignments. Over 12 weeks, all members serve equally in presiding and clerking roles. The 13th week is intentionally different—it is set apart for quarterly conference.

During this 13th week, all 480 quad presidencies gather not as separate units but as a single assembly. They train, realign, and covenant anew. This sacred interruption is not a flaw—it is divine cadence. The imbalance created by 13 is resolved not by resetting but by reunion. Time itself participates in the presidency, just as space does.

The civic calendar is not incidental—it is part of the divine structure. The weeks, seasons, rotations, and rests mirror the design of the heavens and the balance of divine stewardship. The presidency thus becomes an agent of cosmic rhythm.

In every sacred calendar and sky chart, the structure of fourfold time emerges:

– Time rotates—it is not linear

– Divinity governs in quadriune balance

– Seasons, directions, and heavenly symbols all affirm the Four

These celestial patterns validate theology—they do not merely symbolize it. They prove that the divine pattern is not invented but remembered. Farmers saw it. Priests enshrined it. Prophets codified it. And architects built it.

The Quadriune Godhead—Lawgiver, Nurturer, Redeemer, and Counselor—rules the year, the stars, and the civic structure. The sky itself is presidency, written in starlight.

References – Section IVb

1. E.C. Krupp, Echoes of the Ancient Skies: The Astronomy of Lost Civilizations (Oxford University Press, 1983).

2. Anthony F. Aveni, Empires of Time (University Press of Colorado, 2002).

3. Giorgio de Santillana and Hertha von Dechend, Hamlet’s Mill (David R. Godine, 1977).

4. David Ulansey, The Origins of the Mithraic Mysteries (Oxford University Press, 1989).

5. Edwin C. Burrows, The Tetramorph and Ezekiel’s Vision (Cambridge Theology Journal, 1964).

6. Bradley T. Lepper, Ohio Archaeology (Orange Frazer Press, 2005).

7. Charles H. Long, Significations: Signs, Symbols, and Images in the Interpretation of Religion (Fortress Press, 1986).

Section IVc: Universal Quads in Psychology, Philosophy, and Human Structure

The Quadriune pattern is not only evident in architecture, calendar, and astronomy—it is embedded in the very structure of human consciousness, governance, ritual, and science. In this section, we explore how fours dominate in anthropology, theology, logic, and symbolism, providing strong, often overlooked, testimony that the universe is designed to be governed—and understood—by a presidency of Four.

The human body is a biological expression of fourfold design:

– Two arms and two legs

– Two eyes and two ears

– Four heart chambers and four blood types

In sacred traditions, this quadrature becomes symbolic. The Hebrew name for God (YHWH) appears fourfold and is mirrored in Ezekiel’s vision of the four-faced creature—man, lion, ox, eagle (Ezekiel 1:10). These same four faces surround the divine throne in Revelation 4:6–8.

Jungian psychologist Carl Jung identified four major archetypes in the psyche: Self, Shadow, Anima/Animus, and Persona. These map neatly onto the divine functions:

– Self (Counselor)

– Shadow (Redeemer)

– Persona (Lawgiver)

– Anima (Nurturer)

Jung observed these fourfold archetypes emerging spontaneously in dreams, rituals, and trauma recovery, especially in quadrated mandalas. He called them ‘a spontaneous symbol of psychic wholeness’ (Jung, 1964).

Christian liturgy often follows a four-part structure: Confession (Redeemer), Word (Counselor), Eucharist (Nurturer), and Commissioning (Lawgiver). In the Jewish Passover Seder, four ritual elements define the observance: four cups of wine, four questions, and four sons—each reflecting relational roles in covenantal society.

Native American medicine wheels and pipe ceremonies honor the Four Directions with offerings of tobacco, sage, sweetgrass, and cedar—each mapped to a quadrant of divine expression and human identity (Deloria, 1994). Hindu puja (worship) rituals include offerings at four directional altars, completing an elemental whole.

Aristotle’s Four Causes explain not only how things exist but why they matter:

– Material (Nurturer)

– Formal (Counselor)

– Efficient (Lawgiver)

– Final (Redeemer)

These causes correlate to the functions of the Godhead in sustaining, designing, enacting, and fulfilling creation. In Buddhist practice, the Four Noble Truths define spiritual healing, and the Four Vedic Aims (Purusharthas) map duty, prosperity, desire, and liberation across the full life cycle.

Political systems also reflect quadrature. The Roman Republic balanced consuls, senate, tribunes, and religious office. The Iroquois Confederacy’s Great Law of Peace structured fourfold governance across tribal coalitions, with balanced councils and gendered roles of leadership and memory (Mann, 2000).

Modern democratic systems retain this intuition:

– U.S. governance: Executive, Legislative, Judicial, Press

– Global structure: Health (WHO), Knowledge (UNESCO), Justice (UNHCR), Food (FAO)

– Education: STEM, Humanities, Arts, Civics

Sacred geometry reinforces the pattern. Mandalas from Tibet, Navajo sand paintings, Islamic tiling, and Christian rose windows all construct divine space around fourfold symmetry. The tetrahedron—the simplest 3D Platonic solid—embodies stable unity from four equal faces (Michell, 2008).

Mayan cosmology describes four Trees of Creation and four epochs, each governed by divine presences. The center is always a place of convergence, but the structure is quadrated. The same is seen in the Chinese Five Element model, where the fifth element (center) arises from balance among the four.

These patterns—from psyche to polity, from ritual to reason—testify that the deepest operating logic of human and divine life is not dual, not triadic, but quadriune. The Lawgiver, Nurturer, Redeemer, and Counselor are not roles imposed on the Godhead—they are functions remembered by creation.

We are born into a world governed by Four. We think, pray, move, and serve in quadrants. We build in squares, dream in crosses, and heal in mandalas. This is not coincidence. It is memory—written in the very order of life.

References – Section IVc

1. Carl Jung, Man and His Symbols (Doubleday, 1964), pp. 215–237.

2. Vine Deloria Jr., God Is Red: A Native View of Religion (Fulcrum Publishing, 1994).

3. Barbara Alice Mann, Iroquoian Women: The Gantowisas (Peter Lang, 2000).

4. Mircea Eliade, The Sacred and the Profane (Harcourt, 1959).

5. Huston Smith, The World’s Religions (HarperOne, 2009).

6. John Michell, The Dimensions of Paradise (Inner Traditions, 2008).

7. Joseph Campbell, The Hero with a Thousand Faces (Princeton University Press, 2004).

Section IVd: Additional Witnesses of the Four

While architecture, time, psychology, and cosmology already reveal the deep imprint of quadriune design, further corroborating evidence emerges from an even broader range of domains—art, science, linguistics, music, and sacred literature. These lesser-known witnesses extend the reach of the Four into all dimensions of human and divine expression.

Many religious and cosmological systems associate colors with the Four Directions, Four Elements, and Four Divine Presences:

– Native American medicine wheels: red (east), yellow (south), black (west), white (north)

– Hindu Tantric yantras: blue (air), red (fire), green (earth), white (water)

– Kongo cosmograms: four rays crossing at a center point, often color-coded

Color symbolism reinforces the theological function:

– White = Lawgiver (purity, north)

– Yellow = Nurturer (abundance, south)

– Red = Redeemer (blood, east)

– Black = Counselor (mystery, west)

Western music theory organizes harmony around four primary voices: soprano (vision), alto (comfort), tenor (reason), and bass (foundation). Sacred choral traditions—whether Gregorian chant, gospel quartets, or LDS ensembles—use four-part harmony to model divine balance.

In Tibetan ritual, four ceremonial instruments—trumpet, drum, bell, cymbals—are sounded at the cardinal points of the temple to invoke the gods and cleanse the cosmos, forming a sonic presidency.

Biblical and apocalyptic texts frequently utilize quadrature:

– Ezekiel 1 and Revelation 4: four living creatures surround the throne

– 1 Nephi: fourfold vision of tree, iron rod, mist of darkness, and great and spacious building

– Daniel and Enoch: sequences of four empires before divine rule

In the Jewish Merkabah tradition, four ascending palaces precede the presence of the divine chariot. Mystical ascent is quadrated.

Communication theory echoes this structure. Claude Shannon’s model identifies four key components: sender, message, channel, and receiver. Saussure’s semiotic model includes signifier, signified, referent, and interpreter—each needed for meaning.

In logic and computation, four-output matrices define decision trees and binary logic. In science, four fundamental forces govern the known universe: gravity, electromagnetism, strong nuclear, and weak nuclear.

Carbon, the foundation of life, bonds in four directions. Every protein and organic compound depends on the stability of fourfold molecular geometry. The tetrahedron, with four equal faces, is the first Platonic solid in three dimensions—symbolizing stable unity.

Mandalas, sacred wheels, and temple tilings in Buddhism, Christianity, Islam, and Indigenous cultures share a common geometry: four gates, four arms, four steps, or four quadrants converging on a center.

The Four appear not only in high theology, but in fiber, frequency, function, and form. They govern how we build, how we speak, how we hear, how we heal. These are not coincidences. They are the echoes of a memory too ancient to name—the memory of the Godhead who governs all things in balanced presidency.

References – Section IVd

1. Mircea Eliade, The Sacred and the Profane (Harcourt, 1959).

2. Carl Jung, Man and His Symbols (Doubleday, 1964), pp. 215–237.

3. Vine Deloria Jr., God Is Red (Fulcrum Publishing, 1994).

4. Claude Shannon, A Mathematical Theory of Communication (Bell System Technical Journal, 1948).

5. Ferdinand de Saussure, Course in General Linguistics (McGraw-Hill, 1966).

6. Huston Smith, The World’s Religions (HarperOne, 2009).

7. John Michell, The Dimensions of Paradise (Inner Traditions, 2008).

8. Barbara Alice Mann, Iroquoian Women: The Gantowisas (Peter Lang, 2000).

9. Anthony F. Aveni, Skywatchers of Ancient Mexico (University of Texas Press, 2001).

Section V: Taoist and Chinese Philosophical Structure

The religious-philosophical traditions of ancient China—particularly Taoism (Daoism), early Confucian cosmology, and I Ching divination—offer a sophisticated and internally consistent cosmological vision that mirrors the Quadriune Godhead model.

Though often framed in impersonal metaphysical language rather than anthropomorphic deities, Chinese systems of thought emphasize balance, reciprocity, and complementarity as essential to cosmic and moral order. Embedded within these traditions are four interdependent forces or archetypes expressed through nature, energy, personality, and ritual function.

The foundational text of Taoism, the Tao Te Ching, opens:

> “The Tao gave birth to the One. The One gave birth to Two. The Two gave birth to Three. The Three gave birth to the Ten Thousand Things.” (Tao Te Ching, Chapter 42)[1]

Traditionally interpreted as the cosmological movement from undifferentiated being (Tao) to multiplicity, many commentators noted that the “Three” implied Heaven, Earth, and Humanity—but also concealed a fourth principle, the Spirit (shen) that animates and harmonizes the triad.[2]

In later Taoist and Neo-Confucian interpretation, this logic unfolds into a structured tetrad:

– Tian (Heaven) – Principle of order, decree, and cosmic hierarchy (lawgiver);

– Di (Earth) – Generative ground, nurturing and sustaining (nurturer);

– Ren (Humanity/Man) – The active agent, responsible for restoring balance (redeemer);

– Shen (Spirit) – Invisible harmonizer, inspirer, and connector of all things (counselor).[3]

The I Ching describes creation and life in terms of yin and yang—not as a binary, but interacting through four symbolic combinations:

– Greater Yin (old yin),

– Lesser Yin (young yin),

– Greater Yang (old yang),

– Lesser Yang (young yang).

These four expressions form the basis of the 64 hexagrams. They represent lawgiver (yang), nurturer (yin), redeemer (dynamic interplay), and counselor (transformer or balancer).[4]

In Taoist internal alchemy and traditional Chinese medicine, shen represents the spiritual soul, associated with the heart and higher consciousness. It governs clarity, wisdom, and divine inspiration. Shen is cultivated through meditation, ritual, and moral self-discipline.[5]

Chinese cosmology, though not theistic in the Western sense, affirms a constitutional balance of roles and interrelations. The divine reveals itself in functions, not centralized authority.

Practical manifestations of this tetrad are seen in:

– Feng shui: four celestial animals aligned to cardinal directions.

– Confucian rites: honoring Heaven, Earth, Ancestors, and Spirits.

– Traditional Chinese Medicine: Heart (Shen), Liver (Hun), Lungs (Po), and Kidneys (Zhi)—governing moral, mental, emotional, and willful faculties.[6]

In all domains—spiritual, medical, political—Chinese civilization embedded the structure of a divine presidency of four.

The Taoist pattern shows that the grammar of heaven has always spoken in fours: source, ground, mediator, inspirer. This is the Quadriune constitution of divine balance.

References – Section V

[1] Laozi (Lao Tzu), Tao Te Ching, trans. D.C. Lau (Penguin Classics, 2009), Chapter 42.

[2] Michael Saso, The Taoist Experience: An Anthology (State University of New York Press, 2000), pp. 28–34.

[3] Tu Weiming, Centrality and Commonality: An Essay on Confucian Religiousness (SUNY Press, 1989), pp. 91–108.

[4] Richard Wilhelm and Cary F. Baynes, trans., The I Ching or Book of Changes (Princeton University Press, 1967), pp. xxviii–xxxiv, 297–315.

[5] Livia Kohn, The Daoist Monastic Manual: A Translation of the Fengdao Kejie (Oxford University Press, 2004), pp. 76–101.

[6] Giovanni Maciocia, The Foundations of Chinese Medicine, 2nd ed. (Elsevier, 2005), pp. 98–125.

Section VI: Hebrew Wisdom, Ruach, and Gnostic Sophia

The Hebrew Bible and the intertestamental literature of Second Temple Judaism preserve one of the clearest theological frameworks for divine plurality outside of polytheistic contexts.

Though fiercely monotheistic in its mature prophetic traditions, the Hebrew scriptures retain complex notions of divine agency, feminine wisdom, and spiritual presence that prefigure the Quadriune pattern.

In parallel, early Christian Gnostic texts, rejected as heretical by orthodox theologians, preserved a theological system with clear fourfold divine roles, including a divine feminine counselor.

The Hebrew word for “spirit” is Ruach (רוּחַ), which is grammatically feminine in Hebrew and consistently used to refer to divine action, breath, inspiration, and presence.

In Genesis 1:2, “The Ruach of God hovered over the face of the waters,” suggesting a nurturing, animating power involved in creation. Scholars such as Phyllis Trible have emphasized the maternal, hovering imagery of this passage—akin to a bird over her young.[1]

The books of Proverbs, Job, and Wisdom of Solomon (in the Apocrypha) introduce Chokhmah (חָכְמָה), or “Wisdom,” as a feminine personified entity.

Proverbs 8 portrays Wisdom as present with God “before the world was formed,” rejoicing always before Him, and “delighting in the human race” (Proverbs 8:30–31).[2]

Wisdom in this role is not a mere attribute, but a co-creator, advisor, and inspirer—precisely the function attributed to the fourth person of the Quadriune Godhead.

Hebrew scripture also depicts a divine council structure.

In 1 Kings 22:19–23, the prophet Micaiah sees “the Lord sitting on his throne, and all the host of heaven standing by him.”

Similar imagery appears in Job 1 and Psalm 82, where God “presides in the divine assembly.”

These scenes suggest a non-singular heavenly court, involving multiple beings who advise, enact, and mediate divine will.[3]

Early Christian Gnostic literature, including the Gospel of Philip, Gospel of the Hebrews, and Apocryphon of John, features Sophia—the Greek word for Wisdom—as a divine feminine personage who operates independently of the male Father and Logos (Word).

In some Gnostic systems, Sophia is the fourth member of the godhead: a feminine energy that guides, teaches, and sustains, but also suffers separation and seeks reconciliation.[4]

In the Gospel of the Hebrews, the Holy Spirit is described as Jesus’ divine mother: “Just now my mother, the Holy Spirit, took me by one of my hairs and carried me to the great mountain Tabor.”[5]

This radical attribution of maternity to the Spirit confirms that some early Christians understood the Holy Spirit as feminine and personal.

Even when later Gnosticism became dualistic or speculative, it preserved the memory of a quadriune schema: Father, Son, Spirit, and Sophia—each with distinct, coeternal roles.

In a Quadriune framework, the Hebrew and Gnostic materials align as follows:

– Lawgiver (Married Male): YHWH (God of Israel) – Judge, ruler, covenant-maker

– Nurturer (Married Female): Ruach Elohim – Creative spirit, sustainer of life

– Redeemer (Single Male): Logos / Christ – Mediator, sacrifice, teacher

– Counselor (Single Female): Wisdom / Sophia – Inspirer, revealer, co-creator, restorer

Thus, even within strict monotheism, the texture of the text retains four roles—differentiated but united, personal but relational, hierarchical in action but not in essence.

The Godhead envisioned by Hebrew poets and mystics was never simple nor strictly male.

It included the hovering Ruach, the wise Sophia, the mediating Logos, and the sovereign YHWH.

Later systems collapsed these into theological dogma.

But the original record—preserved in scripture, midrash, and apocrypha—speaks of a constitution in heaven, one that matches the Quadriune Godhead.

References – Section VI

[1] Phyllis Trible, God and the Rhetoric of Sexuality (Fortress Press, 1978), pp. 12–21.

[2] Michael V. Fox, Proverbs 1–9: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary (Yale University Press, 2000), pp. 276–298.

[3] Margaret Barker, The Great Angel: A Study of Israel’s Second God (Westminster John Knox Press, 1992), pp. 56–73.

[4] Elaine Pagels, The Gnostic Gospels (Random House, 1979), pp. 48–60.

[5] Bentley Layton, The Gnostic Scriptures (Doubleday, 1987), p. 325.

Section VIa: Elohim as the Quadriune Godhead in Hebrew Scripture

The Hebrew word ‘Elohim’ (אֱלֹהִים) is grammatically plural, yet frequently paired with singular verbs and adjectives when referring to the God of Israel. While traditionally explained as a ‘plural of majesty,’ it may instead reflect a collective divine unity. Within a quadriune theological model, ‘Elohim’ may represent a composite unity of four co-equal beings: Lawgiver, Nurturer, Redeemer, and Counselor.

Genesis 1:26 quotes Elohim saying, ‘Let us make man in our image.’ The plural construction has been variously interpreted, but a quadriune model suggests intra-divine conversation among multiple eternal personages.

Hebrew scripture presents personified divine figures who fit this fourfold pattern:

– YHWH: The covenant Father and judge (Isaiah 33:22).

– Ruach Elohim: The Spirit of God, feminine, active in creation (Genesis 1:2).

– Chokhmah: Wisdom, co-creator with God (Proverbs 8).

– Logos or Ben Elohim: Later interpreted as divine Word or Mediator (Isaiah 9:6, John 1).

Psalm 82:1 depicts ‘God (Elohim) standing in the divine assembly,’ reinforcing a vision of plurality-in-unity. The Targums and Midrash further identify various divine figures such as Shekinah (presence) and Metatron (messenger), which suggest roles within a broader Godhead.

A quadriune reading of ‘Elohim’ affirms divine plurality not as polytheism but as constitutional unity—a model echoed in the perichoresis of the early Church and mirrored in the divine quads of world faiths.

Understanding ‘Elohim’ as the collective name of the Quadriune Godhead restores semantic integrity to the plural form and aligns with global patterns of divine fours. It also prepares the foundation for understanding sealing, governance, and civic design as reflections of divine structure—not abstract doctrine, but constitutional theology.

In the context of Section VI of this paper, which traces divine personification through Hebrew and Gnostic tradition, the use of ‘Elohim’ as a fourfold composite deepens the reading of Ruach (Spirit), Chokhmah (Wisdom), Logos (Redeemer), and YHWH (Lawgiver) as the governing whole. ‘Elohim’ is thus not simply a grammatical oddity. It is a scriptural witness to divine presidency.

References – Section VIa

Phyllis Trible, God and the Rhetoric of Sexuality (Fortress Press, 1978).

Michael S. Heiser, The Unseen Realm: Recovering the Supernatural Worldview of the Bible (Lexham Press, 2015).

David L. Paulsen and Roger D. Cook, ‘The Divine Feminine in Early Mormon Theology,’ BYU Studies 46, no. 1 (2007): 79–117.

Richard Elliott Friedman, Who Wrote the Bible? (HarperOne, 1997).

Margaret Barker, The Great Angel: A Study of Israel’s Second God (Westminster John Knox Press, 1992).

Elaine Pagels, The Gnostic Gospels (Random House, 1979).

The Babylonian Talmud, b. Sanhedrin 38b.

The Zohar, Genesis 1, and commentaries on the four rivers of Eden.

Revelation 4; Isaiah 9:6; Proverbs 8:22–31; John 1:1–3.

Section VII: Indigenous Cosmograms and Fourfold Directionality

Among the most globally persistent and spiritually unifying systems of sacred pattern is the Indigenous fourfold cosmogram—a symbol and worldview structure that appears across the Americas, Africa, Oceania, and parts of Asia.

While diverse in application and terminology, these traditions consistently organize space, purpose, and spirituality into a quadriune framework: four sacred directions, four governing spirits or deities, four human archetypes, and four elements of creation.

This model is not peripheral—it is cosmologically central, shaping ceremonies, governance, healing, and education in Indigenous communities.

The Medicine Wheel—used by the Lakota, Ojibwe, Navajo, Zuni, and many others—is both symbol and map. It orients human life to four cardinal directions, each associated with a color, season, animal, and human characteristic:

– East (Yellow): Birth, spring, eagle, mind/spirit (counselor/inspirer);

– South (Red): Youth, summer, coyote, emotions/energy (redeemer);

– West (Black): Maturity, autumn, bear, introspection (lawgiver);

– North (White): Elderhood, winter, buffalo, wisdom and nurture (nurturer).[1]

These quadrants are invoked in ceremonies such as the Sun Dance, sweat lodge, vision quests, and naming rituals. They are represented physically in the arrangement of lodges, tipis, and dance circles. Most importantly, each direction embodies a relational role, not just a space.

Lakota theologian Vine Deloria Jr. explained that Indigenous cosmology is not hierarchical but rotational and seasonal—roles shift, each has its time, and governance is collaborative.[2] The divine is encountered in the interplay of the four, not in the dominance of one.

In Maya and Aztec cosmology, the four cardinal directions anchor the world tree or axis mundi, supporting the heavens. Deities such as Tezcatlipoca, Quetzalcoatl, Xipe Totec, and Huitzilopochtli were assigned to directions and functions: judge, redeemer, inspirer, nurturer.[3]

In Incan religion, the Tahuantinsuyu (Empire of Four Quarters) organized all political and sacred life into suyu—directional quadrants linked to seasons, duties, and divine approval. Each suyu had representative priesthoods, totemic animals, and ecological functions.[4]

In Yoruba cosmology, the Orisha pantheon assigns divine authority across four functional roles:

– Obatala: Creator and judge (lawgiver);

– Yemoja: Ocean mother, fertility, nurture (nurturer);

– Ogun: Warrior, builder, transformer (redeemer);

– Orunmila: Wisdom, divination, foresight (counselor).[5]

These four Orisha appear not as isolated gods, but as partners in creation, invoked at key ritual junctions and encoded into naming, music, healing, and social structure.

Among the Hawaiians and Maori, fourfold models guide navigation, genealogy, and spiritual alignment. The Polynesian ‘aumakua system assigns protective spirits to ancestral lines based on direction, gender, and moral function.[6]

Taro planting, canoe building, and temple design mirror these four poles.

Across Indigenous cultures—despite linguistic, historical, and geographic separation—the structure of divine life is quadriune: four roles, interwoven, dynamic. No one role dominates. Each is sacred.

These systems offer the clearest anthropological confirmation that the Quadriune Godhead is not novel theology, but global sacred memory. Where empire erased, oral tradition remembered. The circle remains.

References – Section VII

[1] Barbara Tedlock, The Woman in the Shaman’s Body (Bantam Books, 2005), pp. 173–197.

[2] Vine Deloria Jr., God Is Red: A Native View of Religion (Fulcrum Publishing, 1992), pp. 103–126.

[3] Davíd Carrasco, Religions of Mesoamerica (Waveland Press, 2013), pp. 54–78.

[4] Gary Urton, Inca Mythology and Empire (University of Texas Press, 1990), pp. 41–63.

[5] Jacob K. Olupona, African Religions: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2014), pp. 57–89.

[6] Martha Beckwith, Hawaiian Mythology (University of Hawaii Press, 1970), pp. 211–239.

Section VIII: Joseph Smith’s Interrupted Revolution – From One to Four

Joseph Smith’s theology of divinity did not emerge fully formed, nor did it remain static. It evolved significantly over the fourteen years of his ministry (1829–1844), progressing through a bold and destabilizing transformation of the nature of God—from monotheistic and modalistic roots to a complex, bodily, and co-equal plurality that neared but never completed the Quadriune Godhead. This section outlines that trajectory with primary revelations and scholarly reference for each stage.

Phase I – Monotheistic Beginnings (1829–1831)

Joseph’s early revelations, especially those recorded in The Book of Mormon (published in 1830), reflect a modalistic monotheism—God is one being, appearing sometimes as the Father, sometimes as the Son. Passages such as 2 Nephi 31:21 and Mosiah 15:1–5 refer to God and Christ as a single being manifest in different roles.[1]

Phase II – Dyadic Separation: Father and Son as Distinct Beings (1832–1835)

In the 1832 First Vision account, Joseph writes that he saw “the Lord,” and soon afterward refers to two personages. By the 1835 account, the narrative explicitly separates the two beings: “two personages whose brightness and glory defy all description.”[2] This is formalized in D&C 76 (1832), which identifies the Son “on the right hand of God.”[3]

Phase III – Triadic Expansion: The Holy Spirit as Third Personage (1835–1836)

In D&C 88 and later in D&C 130:22, Smith taught that the Holy Ghost was a personage of Spirit, distinct from both the Father and Son. This teaching completed a triadic model where the Holy Spirit had independent revelatory and ministerial authority.[4]

Phase IV – Toward a Fourth: The Emergence of the Divine Feminine (1843–1844)

By 1843, Smith began to speak of a Heavenly Mother. While not canonized in a direct revelation, contemporaries such as Eliza R. Snow and W.W. Phelps affirmed that Smith taught the existence of a divine female partner to the Father. Snow’s 1845 hymn, “O My Father,” reflects this doctrine.[5]

Section 94 – The Four Courts of Instruction

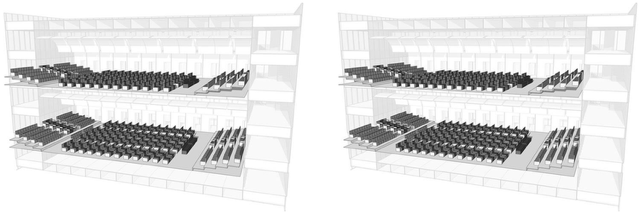

Doctrine and Covenants 94, received May 6, 1833, commanded the construction of two buildings, each identical and each with a lower and higher court, totaling four courts. These were assembly spaces for the quarterly conferences where 480 presidents from each divisional demographic of the community meet to be taught by each of their 24 demographic presidents. The design matches a quadriune pattern of stewardship and balance, not hierarchy.[6] The early LDS saints went broke completing part of only one of the buildings and that building known as the Kirtland Temple in Kirtland Ohio still exists.

The building (Photo below) has two identical higher and lower courts, but the LDS leaders and historians have not figured out what the two courts are for. The early saints were not ever able to start or complete the second building and so the four courts and their purpose were never implemented.

The first LDS temples followed the lower and upper court pattern but eventually the lower courts were turned into ordinance rooms and the upper courts used as general assembly. The pattern was discontinued after the Salt Lake temple was completed.

A diagram showing what the two buildings each with identical courts would have looked like is below the photo. The lower court of building #5 was for the 480 partnered (married) male presidents. The higher court of building # 5 is for the 480 partnered female presidents. The lower court of building #17 is for the 480 single female presidents. And finally, the higher court of building #17 if for the 480 single male presidents.

The presidents meet quarterly to learn and be taught by each of their 24 demographic agency presidents. They and operate together as 480 presidencies of 4, one from each demographic when serving the community.

April 1836 – Sealing as Networked Kinship

On April 3, 1836, Smith and Cowdery received temple visions (D&C 110). Three days later, they performed the first sealings—adoptions, not marriages—sealing Fanny Alger as a daughter to Joseph and Emma, and Adaline Fuller to Oliver and Elizabeth Cowdery.[7]

Derailment: The intended familiar sealings between parents and children, husbands and wives, friends and associates collapsed into patriarchal Polygamy.

After May 1836, Smith’s sealing model shifted. By 1842–43, the principle of patriarchal marriage took precedence, culminating in Brigham’s edited D&C 132 published 32 years after Josephs death in 1876. The kinship model for the sealing ordinance was replaced by a patriarchal hierarchal model, halting the quadriune trajectory of Joseph Smiths theological revolution.

Conclusion

Joseph Smith was a revolutionary heretic from traditional points of view. His theology evolved from a godhead of one to two, to three, and toward four—represents the closest modern attempt to recover the full ancient divine Godhead of four the Hebrew (Elohim).

References – Section VIII

[1] David L. Paulsen and Roger D. Cook, “The Divine Feminine in Early Mormon Theology,” BYU Studies 46, no. 1 (2007): 79–117.

[2] Dean C. Jessee, ed., The Personal Writings of Joseph Smith, rev. ed. (Deseret Book, 2002), pp. 4–6.

[3] Doctrine and Covenants 76:20.

[4] Doctrine and Covenants 130:22; 88:4–13.

[5] Eliza R. Snow, “O My Father,” Times and Seasons, Nov. 15, 1845.

[6] William G. Hartley, “Kirtland Temple: Its Design and Construction,” Ensign, March 1971, pp. 16–21.

[7] Brian C. Hales, Joseph Smith’s Polygamy: History and Theology, Vol. 1 (Greg Kofford Books, 2013), pp. 56–78.

Section IX: Sealing as Divine Belonging

Among Joseph Smith’s most original theological contributions was the doctrine of sealing—a form of spiritual linkage that went beyond marital union to establish eternal bonds between individuals and God.

Though later transformed into a patriarchal and polygamous institution, the earliest sealings reveal an intent far closer to the framework of the Quadriune Godhead: an eternal community in which all individuals are sealed into divine kinship, regardless of gender, biology, or marital status.

On April 3, 1836, Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery received a vision of Jesus Christ, Moses, Elias, and Elijah in the Kirtland Temple (D&C 110). This vision marked the formal restoration of sealing keys, specifically connected to “the hearts of the fathers to the children” (v.15). Immediately afterward, on April 6, 1836, the first recorded sealings took place:

– Fanny Alger was sealed as an adopted daughter to Joseph and Emma Smith;

– Adaline Fuller was sealed to Oliver and Elizabeth Cowdery.[1]

These were not marriages, nor were they predicated on biological lineage. Rather, they were spiritual adoptions—acts that defined eternal family not through reproduction or possession, but through covenantal connection.

Smith taught that all people must eventually be sealed to one another in a great “welding link” (D&C 128:18). He declared:

> “It is necessary in the ushering in of the dispensation of the fullness of times… that a whole and complete and perfect union, and welding together of dispensations, and keys, and powers, and glories should take place.”

This vision points not to hierarchy but to interconnection. The sealing principle, at its origin, was inclusive, multilateral, and spiritually egalitarian. Within the Quadriune Godhead, each person is eternally sealed to the others:

– The Father is sealed to the Mother;

– The Son is sealed to the Spirit;

– All four are sealed to one another in divine unity.

This sealing is not defined by marriage or dominion, but by function and eternal loyalty. Sealing reflects the perichoresis or mutual indwelling found in early Christian thought, now expanded to a four-person Godhead.

In its original application, sealing offered a theology of belonging to those who might otherwise remain isolated:

– Children without posterity could be sealed to adoptive parents.

– Single individuals—including the Son and Spirit—could be sealed into the divine household.

– Friendships, stewardships, and prophetic commissions could be sealed through covenant. Many early sealings included sealings between men as an expression of their love and kinship with the Godhead and their eternal bond with each other.

This radically inclusive model reflects ancient patterns. In early Christianity, spiritual kinship (adelphoi) often took precedence over biology. In Roman law, adoption conferred full legal standing. In Hebrew scripture, figures like Elijah and Elisha functioned as covenantal kin.

In the sealing pattern Joseph introduced, all are adopted into the House of God—not merely symbolically, but ontologically. We are to become one family of Four, sealed into divine governance, love, and purpose.

By 1842–76, the sealing principle had been co-opted into plural marriage, formalized in much later by Brigham Young in 1876 with D&C 132. The original concept of spiritual adoption gave way to a lineal theology, where women and children were sealed to priesthood holders in vertical chains of authority.

Where once sealing represented horizontal kinship, it became an instrument of patriarchal consolidation. The Spirit and Son—the single divine persons—were replaced in practical theology with eternal couples. The vision of the Quadriune was erased.

Sealing was never meant to be marital only. It was a cosmic covenant, reflecting the very constitution of heaven. The four persons of the Godhead are not only co-equal—they are inter-sealed, bound eternally in roles that encompass every human condition: male and female, married and single, parent and child, friend and friend, teacher and friend and on and on until all are sealed to GOD who are a united body of four.

To restore the sealing principle is to restore divine belonging—to knit humanity into the pattern of Four that governs the universe.

References – Section IX

[1] Brian C. Hales, Joseph Smith’s Polygamy: History and Theology, Vol. 1 (Greg Kofford Books, 2013), pp. 56–78.

[2] Doctrine and Covenants 128:18.

[3] Samuel M. Brown, In Heaven as It Is on Earth: Joseph Smith and the Early Mormon Conquest of Death (Oxford University Press, 2012), pp. 151–176.

[4] Terryl Givens, Wrestling the Angel: The Foundations of Mormon Thought (Oxford University Press, 2015), pp. 314–333.

[5] Kathleen Flake, “Translating Time: The Nature and Function of Joseph Smith’s Narrative Canon,” Journal of Religion 87, no. 4 (2007): 497–527.

Section X: The Quadriune Pattern as Universal Governance

Joseph Smith’s evolving doctrine of God moved through a dramatic and unprecedented progression: from one (a modalistic monotheism in early Book of Mormon texts), to two (Father and Son, clarified by his First Vision and D&C 76), to three (explicitly including the Holy Spirit in D&C 130), and finally toward four (the Heavenly Mother, affirmed by Eliza R. Snow’s 1845 hymn and supported by architectural and administrative revelations such as D&C 94).

This theological arc was not unique to Latter-day Saint scripture. As explored throughout this volume, the quadriune structure of divinity appears across traditions worldwide.

In ancient Sumer: An, Ki, Enlil, Inanna. In Egyptian Osirian theology: Osiris, Isis, Horus, Ma’at. In Hinduism: Vishnu, Lakshmi, Krishna, Saraswati. In Taoist cosmology: Tian, Di, Ren, Shen. In the Hebrew canon and Gnostic tradition: YHWH, Ruach, Logos, Wisdom. And across Indigenous cosmograms from the Americas and Africa: Obatala, Yemoja, Ogun, Orunmila.

These sources confirm that the Quadriune Godhead is not innovation, but restoration. Joseph’s genius lay in glimpsing this divine presidency—and attempting, however imperfectly, to instantiate it.

What Joseph nearly recovered, and what earlier civilizations hinted at, is not just theological—it is constitutional. The four-person presidency reflects a structure of governance rooted not in dominance or seniority but in diversity, balance, and rotating stewardship.

Each quad reflects the core conditions of human life:

– Lawgiver (often married male)

– Nurturer (married female)

– Redeemer (single male)

– Counselor (single female)

This fourfold system appears in the governance model outlined in Joseph Smith’s Law of 1831 and Plat of Zion, which describe civic communities organized into 24 independent agencies, each with a four-person presidency.

In total, each Zion community of 100,000 includes:

– 480 quad presidencies of the community in general

– 960 quad presidencies for the 960 branches

– 1,440 presidencies and 5,760 public stewards—most part-time and all unpaid, nonhierarchical.

This is not conjecture. It is administrative law, grounded in property deeds, investment returns, and structured rotation.

The community envisioned by the LAW is not a church. It is not religious. It is an economic and civic order that honors the divine pattern in its social design. It does not require belief to function—only participation, stewardship, and service.

Across the world, this fourfold pattern has been encoded into public architecture, symbolic diagrams, oral traditions, and state liturgies:

– In Egypt, temples depicted Osiris, Isis, Horus, and Ma’at—governing together.

– In Vedic India, Brahma, Vishnu, Lakshmi, and Saraswati appear in mutual support.

– In Confucian China, Heaven, Earth, Humanity, and Spirit formed the basis of governance.

– In Andean, Yoruba, and Lakota systems, fourfold balance governs space, time, healing, and leadership.

These patterns are not religious mandates. They are social archetypes—reflections of divine symmetry applied to human order.

Joseph Smith did not complete the restoration. But he saw the template. He wrote it into the LAW. He drew it into the Plat. And through Section 94, he received instruction to build it—four equal courts for the public servants to meet in quarterly, patterned after a divine presidency of Four.

The Quadriune is not metaphor. It is structure. It governs not just heaven but any society willing to reflect it.

And unto you, the Kingdom is given.